|

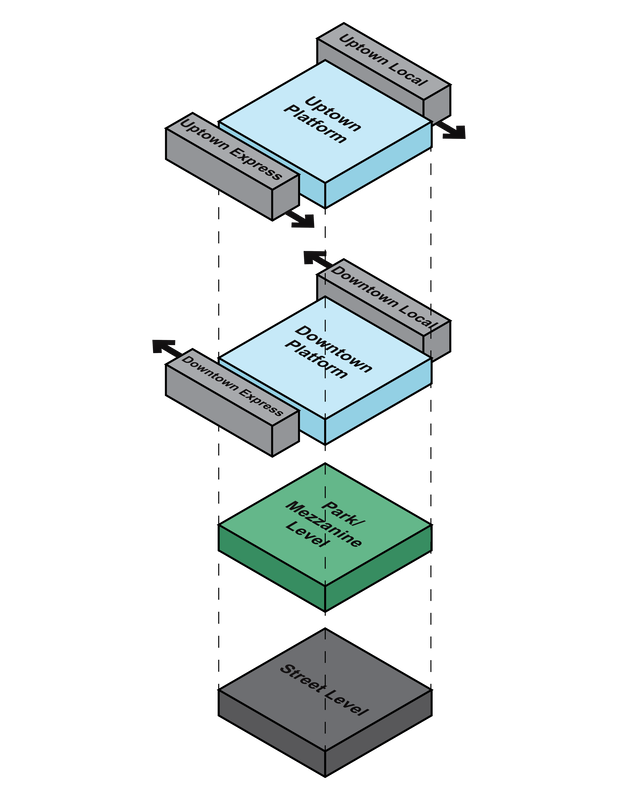

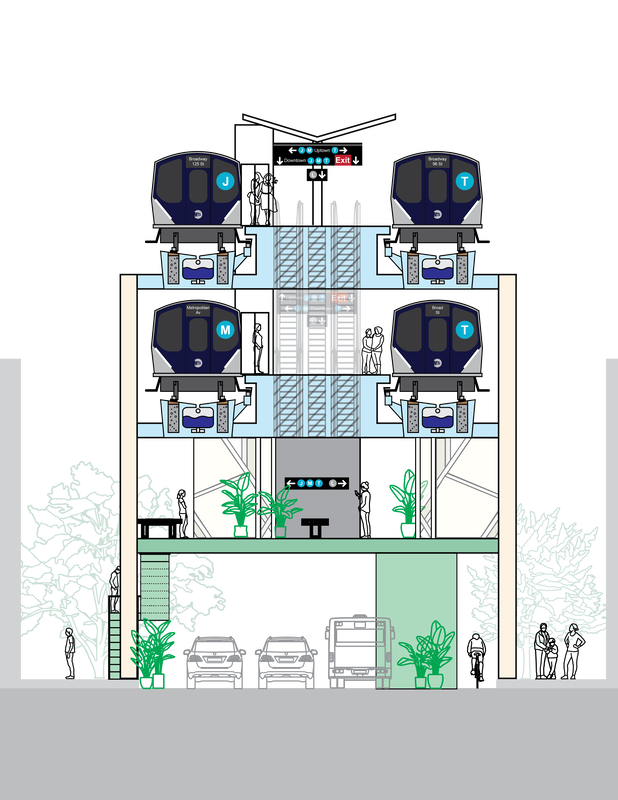

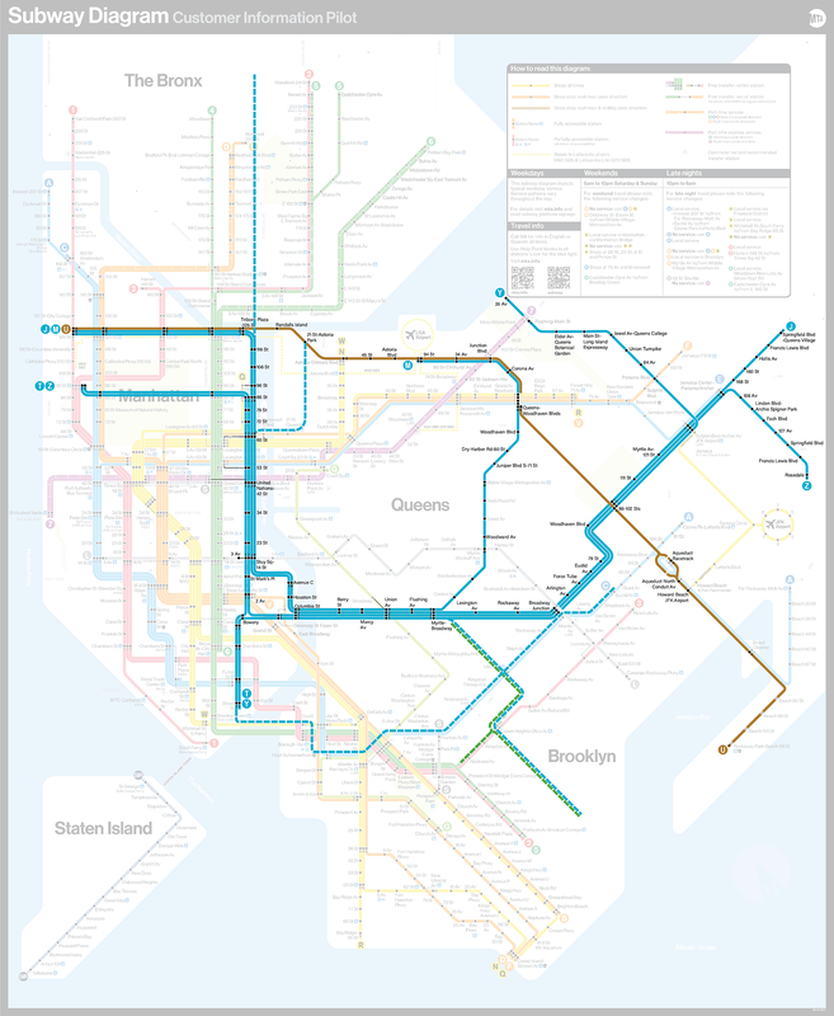

As a senior in the Barnard + Columbia Architecture program, I created a proposal for a system of elevated subways that interacted with street life in a way that intertwines public space and city programs with transit. This system is designed in such a way that it proposes a livable, sustainable, and engaging method of constructing elevated train structures in contrast to the current elevated lines that exist in NYC today. Click the button below to read the full report, or keep on reading for a brief overview! One of the biggest question that such a proposal evokes is: "why build a new elevated train in the first place?" I'm not sure this has any "right" answer, and a lot of the reasoning is up to the specific circumstances and site conditions for a particular project. But if I had to explain it succinctly, the answer is that especially in NYC, we are living in a world where mass transit projects are astronomically expensive, insufficient to combat the rising threat of climate change, and lacking in a true integration of street life and transit modes. These dual programs--street life and transit--lie at the crux of the ESS project, and the proposal I created is a method of thoroughly integrating these two elements to create a transportation system that responds to the impulses and needs of a dynamic city. When building underground becomes prohibitively expensive and unideal from a programmatic design perspective, perhaps the only viable alternative is to try and construct a livable elevated structure. The long answer to why and how to build elevated trains is the topic of lengthy discussion in the full ESS book, some of which I've compiled below: Though not explicitly stated, the logic of transit station placement is based on the presence of public spaces such as squares or plazas. For example, planners during the construction of the first subway in NYC chose to mainly follow both major cross streets as well as nearby public squares. There is no information on why exactly they chose these locations, or at least none of which I’m aware, but it is certainly logical to conclude that the reasoning has somewhat to do with how pedestrians move around the city. Most commercial corridoors are along major cross streets, so it seems reasonable to locate a subway station there. Public plazas and squares are not all commercial spaces, but they all do serve as gathering spaces for large masses of people. For example, many of the stations on the first subway route (City Hall, Spring St, Astor Pl, 14 St-Union Sq, Times Sq, Columbus Circle, 66 St, 72 St, and 137 St) all serve to both supplement and bolster street life by associating themselves heavily with public spaces. This provides a compelling argument for the fact that historically, the planning and functioning of transit infrastructure is heavily related to the presence of public spaces. Subways derive greater ridership by placing stations where people are likely to gather. At the same time, public spaces are much more likely to have lively activity when there is a transit connection nearby. The current 2nd Avenue subway plan is not immune to political games, and this is evident in the FEIS (Final Environmental Impact Statement). This study was completed in 2004, and it is quite out of date, especially considering that the study says the full 2nd Avenue subway would be complete by 2020. One of the many issues there are with the report is that it makes no effort to build a transfer between 59th Street Lexington Avenue. This would give 2nd Avenue much better access to Queens. In fact, the proposed line includes a track connection to the 63rd Street tunnel for Queens-Manhattan service south of 59th Street despite making no efforts to utilize this in revenue service. This demonstrates a much larger issue with the planning of the subway line as a whole. Its Manhattan-centric focus is likely the result of specific interests that want to keep 2nd Avenue a distinctly Manhattan route. In fact, if the Q train wasn’t necessary for phases 1 and 2, then the Q would have likely never interacted with 2nd Avenue. Despite the fact that the construction of a 2nd Avenue line would increase the system’s overall capacity, it is constrained solely to the east side, much of which is now wealthier. It is a deliberate attempt at spatial segregation as much as is possible in a city like New York. Another example of this racist and classist intention is the planning of the lower Manhattan section, which already has numerous stations. The real reason the FEIS chose the alternative of building new stations is likely because it would further serve the Financial District of Manhattan. This option would increase development and property values of people who are already very influential, which is not the best use of transit funding. The three most important factors that affect the country’s transit needs going forward are the following: the shift in the way people get to and from work, making up for past discriminatory transit projects, and the impact that transit has on the environment. The first of such stems from the idea that in the past, “people in search of employment [would be] straying ever further from their residences” (Schaffer and Sclar 3). For an urban model based on the fact that people would live in the outskirts of a city and commute into the center, a traditional hub and spoke transit model works fairly well. In NYC, this resulted in a system that makes it very easy to travel to Manhattan, the center of the city, but much harder to travel between the outer boroughs. Now, especially with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, more and more residents are choosing to either work from home or work in areas outside of Manhattan. This requires a completely different transportation network, one that looks more like an interconnected web, which would allow for easy transit to and from any point in the city. The most important aspects to getting government to create such a transit system in the contemporary era includes attaining political will, ensuring home values, preventing or mitigating gentrification, and minimizing construction disruptions. To the first, the recent change in both mayoral and gubernatorial leadership in New York present promising signs, especially with the advent of the Interborough Express project. Any transit project in NYC will also necessarily increase home values due to proximity to transit being a key factor in worth. However, residents who live directly adjacent to the new transit line may have concerns about the physical infrastructure of the transit line creating a decrease in the value of their home. This is due to the existing connotations of what elevated trains bring to a street: noise, lower amounts of light, unhospitable urban environments, etc. These concerns will come down to how the structure itself is designed. Going off the notion that transit should be intrinsically linked with freedom, there is also an idea that the physical infrastructure of transit can be one of the factors that increases an individual person’s connection and interaction with the streetscape and neighborhood as a whole. This project should also aim to provide more greenspace and communal plazas to neighborhoods, space for small businesses to open smaller-scale locations that mitigate the marginal cost of operation, and any other programs that each neighborhood can decide. Ideally, this would give neighborhoods and local communities the opportunities to add more space for the functions that they deem necessary or important to that specific place. Mitigating the effects of gentrification are also deep concerns, especially in low income and minority communities. The fear is that the presence of a new transit line might increase the construction of luxury and unaffordable apartments in their neighborhoods, which would then drive out longtime residents. While there are many approaches to designing policies that counteract the effects of gentrification, it should be noted that the development of new transit lines will always increase and incentivize development. If there are policies that can control what kind of development is built, then it will be much easier to keep longtime residents in their own neighborhoods. Rezoning of certain areas can be part of the solution. To the last point about minimizing construction disruptions, the design of the ESS transit project could also use modular and prefabricated building techniques. These would help make the construction process much faster and less disruptive, meaning construction crews won’t have to be on site for a very long time, like in traditional subway construction. One seemingly unavoidable problem with elevated transit in NYC right now is the terrible conditions it creates for residents who live right next to the train. However, the case study section of this project clearly demonstrated that this doesn’t have to be the case. We can design elevated transit options in a manner that creates little disturbance to the street, and it boils down to three main aspects: noise, shadows, and circulation space. Before delving into each of those topics, it’s important to outline how the ESS structure will be arranged. The diagram to the right shows a breakdown of how the different levels would work. Just above the street, there will be a park level, which is intended to add greenspace to the street level below. By integrating the park and street levels thoroughly, it should provide a seamless transition for pedestrians, and the new park level will become a natural extension of the street. The park level will also include mezzanine space when there is a transit station. I positioned the uptown level as the highest floor because most people will likely be traveling in the downtown direction when they enter a station. Although it certainly won’t be the case for everyone, and even though it seems a little presumptuous, this arrangement will hopefully satisfy the most amount of people possible. Circulation between the levels will make liberal use of elevators and escalators, so even if it does not seem ideal, it will hopefully not become too much of a burden for all travelers. This method is also in use on the Central Park West Line (A, C, B, D), so it has some precedent in the existing system. In an attempt to reduce noise, the trackways themselves will include sound-absorbing material below each individual rail, in an effort to reduce the noise from the metal train wheels. More on the specifics of the trackways will be on the next page. Throughout the ESS system, curves will be limited to a minimum curve radius of 350 ft, which will eliminate much of the screeching that happens on tight turns. In a lot of instances, this requires having the trackways go over existing structures via transit easements. The benefits of having larger curve radii outweighs the costs of extra screeching noises and slow service frequency from shorter curve radii. The transit easements will not include any instances where the structure will need to occupy existing building space as well-- columns will only occupy existing street right of ways. Because the structure never physically touches these buildings, they should feel no disturbances. With these techniques, the noise that the trains create should be less than that of cars on the street. If we condone noise pollution from cars, surely minimal noise pollution from trains should be acceptable. In fact, the presence of an ESS structure should hopefully reduce car traffic on the street, so overall noise levels should never be higher than existing levels. This does mean that the ESS plan will take away car lanes, which would seemingly reduce efficiency of other transit modes. However, by moving more people to mass transit, the ESS plan should provide a net increase in efficiency for all transit modes. Lastly, the ESS structure will have very light cladding and exterior finishes to reduce the shadows they create. The trackways will be designed to have the smallest width possible to provide a very small footprint, and their light blue paint color will be slightly reflective to imitate the brightness of the sky. New York City has the highest per capita public transit ridership of any American city, and yet, the state of such infrastructure is rather poor. The system feels dated, and far too many stations still feel unwelcoming. This is not to say that government agencies aren’t enacting any change to alleviate New York’s transportation woes. Phase 2 of the MTA 2 Avenue subway plan is currently in the engineering phase and the state expects construction to start soon. However, a history of political infighting, insanely high prices, and long waits for the completion of infrastructure projects means that current solutions can not keep up with current needs for transit improvements. For the amount of people that use public transportation in New York City, our investment in those systems is far to small. After living through two years of a global pandemic, New York City is seeing a slow return of workers to office buildings. However, the pandemic will likely change commuting patterns for the foreseeable future, as more and more individuals will likely choose to either work from home or engage in different activities that require alternate transit patterns. The age of work-centered cities is over; although some people will continue to commute from the outskirts into the central business district, it is much more likely that commuters will choose to travel either between boroughs or in ways that transit planners just ten years ago wouldn’t have imagined. Such a change requires our transit system to be resilient and adapt to the changing needs of residents very quickly, and the rate at which transit infrastructure projects have progressed does not bode well for this new pattern. Concerningly, the pandemic has made more and more people feel unsafe taking public transit, and current disinvestments in the physical spaces continues to perpetuate this dynamic. New York City is unique in that the subway is, in many ways, an extension of street space. The same communal activities of gathering, watching performances, and meeting people are as prevalent in the underground mezzanines as they are in the public squares above. For New York, the subway is a microcosm of the city, and to lose this vital communal space to a culture of car-centric transportation would be devastating. We can sit back and concede that public transit isn’t worth investing money, and that the problems that the system faces are inconceivably difficult to rectify. We can turn away from the aspects of city life that make New York such a dynamic place and fill the remaining underground void with safety policies that have no solid history of positive gain. We can abandon our collective responsibility to creating a welcoming urban environment, but that is not worthy of New York, it is not worthy of the people, it is not worthy of our culture. What we need is an unparalleled commitment to bettering our public transportation systems that is equal to the Federal Highway Act of 1956, where our government helped build highways across the length and breadth of America with the hopes of improving infrastructure on an insane scale. What’s more is that we need a steadfast obligation to all people, regardless of race or class, that they should be able to go anywhere at any time and to no detriment of their own communities. We need a fundamentally antiracist transit system that uplifts those most marginalized and ensures that they get the quality transportation that they deserve. We must focus on building communities up and increasing quality human interactions rather relying on the individualistic and self-centered transit modes that America has come to embrace. The ESS plan, if implemented, will represent a reversal in character of past transit investments to create a system that imagines a robust transit network. Even if it doesn’t end up in any physical space, my hope is that by proposing such a drastic and innovative system, politicians will start looking up towards our collective potential rather than settling on the insufficiency of existing policy efforts. Likewise, I implore citizens to look at this project as a bold representation of the transit investments we expect of our elected representatives. Though people will likely debate the exact details and designs of the ESS plan, it represents a continuation of the community-centric nature of our current transportation system that focuses on highlighting the best aspects of New York City’s culture. The following image shows a broad vision of the sheer extent to which New York could take the ESS system. It represents simply the breadth of options that a new and improved 2 Avenue subway could become if every derivative option is exercised. This is not a prescriptive plan; it does not represent what should exist. Rather, it represents the sheer scope and potential for such a transit project.  Thank you to everyone I interviewed, for your insight and help on this project: Andrew Lynch (Vanshnookenraggen), Alon Levy, Tiffany-Ann Taylor, Mary Rocco, Kadambari Baxi, Alan Hoffman.

Special thanks to Ralph Ghoche, my advisor.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2023

Categories |